UKC recently published an article on the 50 year ascent of Paladin in White Ghyll. Paladin was first climbed in September 1970 by my dad (Rob Matheson) and was re-climbed by him in September 2020.

The ‘full text’ and Paladin 50 video is shown below, with questions posed by Nick Brown (UKC). It is included here for those that wish to read a little more about my dads climbing background.

Can you elaborate on your early climbing years. How did you start climbing. What are some of your early climbing memories. How did it differ from climbing today?

When I was 7, my Dad and Uncle let me do some real mountaineering with them and took me up The Cobbler in Arrochar. Not only that, but we did some proper rock climbing, by finishing up the South-East Ridge which was graded Moderate, and we used a proper hemp climbing rope! Of course I was made up, and for the next few years I was desperate to get out on the hills in any capacity. Strangely enough I’ve never been back to The Cobbler!! Shame on me!!

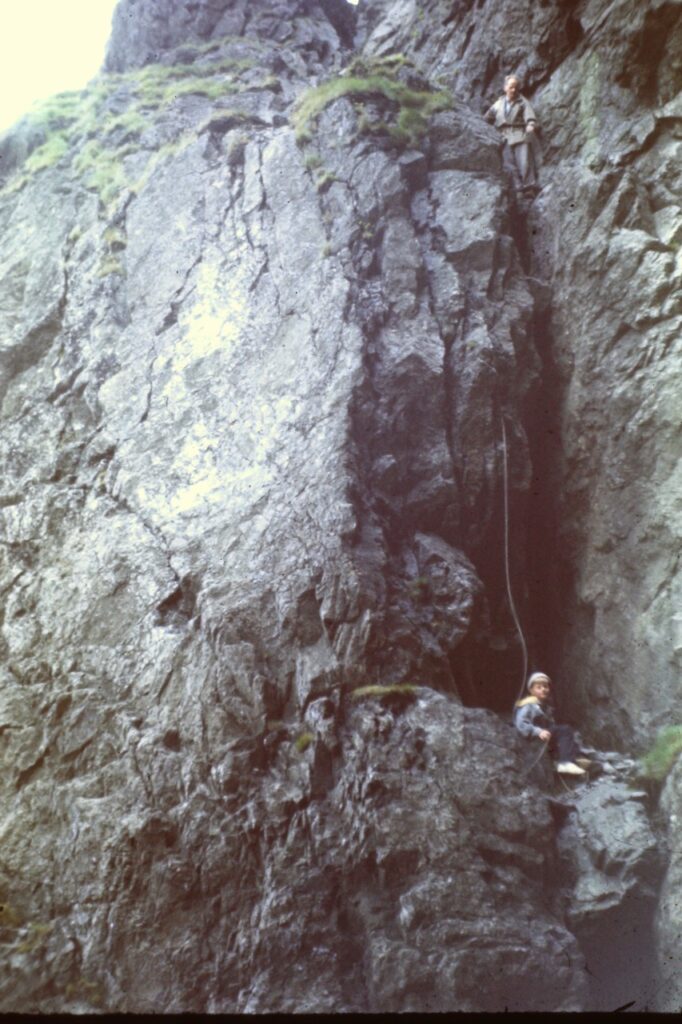

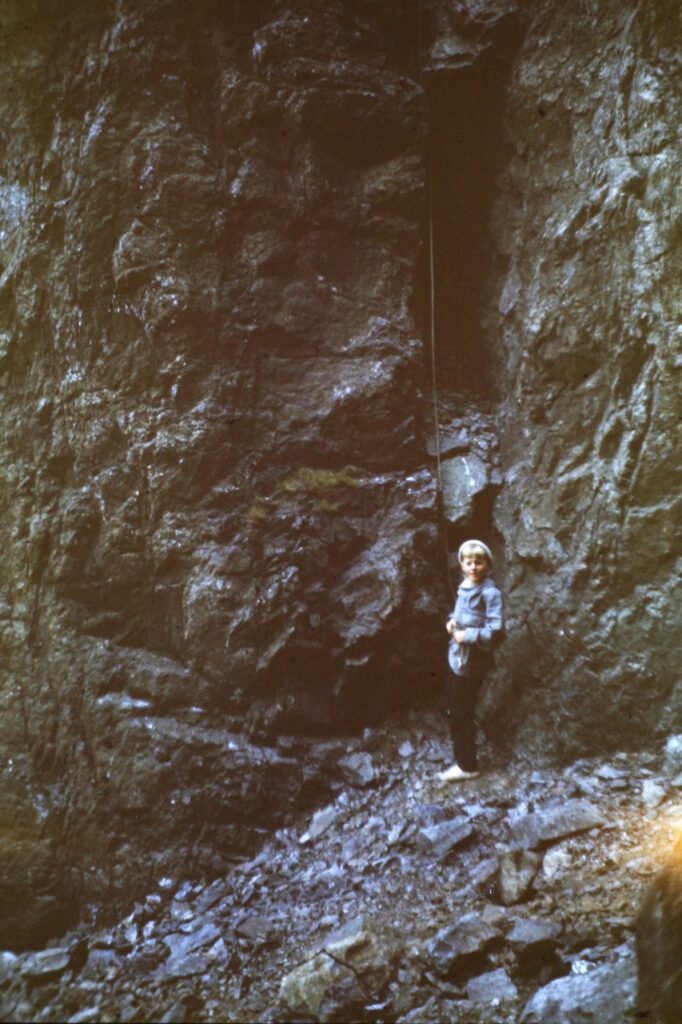

My parents were Scottish but we lived in Barrow, just south of The Lake District, and so the Duddon Valley, Coniston area and Langdale became the regular walking, and ultimately climbing haunts. I remember struggling over the chockstone on South Chimney, a Difficult on Dow Crag, in my pristine white plimsoles, when I was about 10.

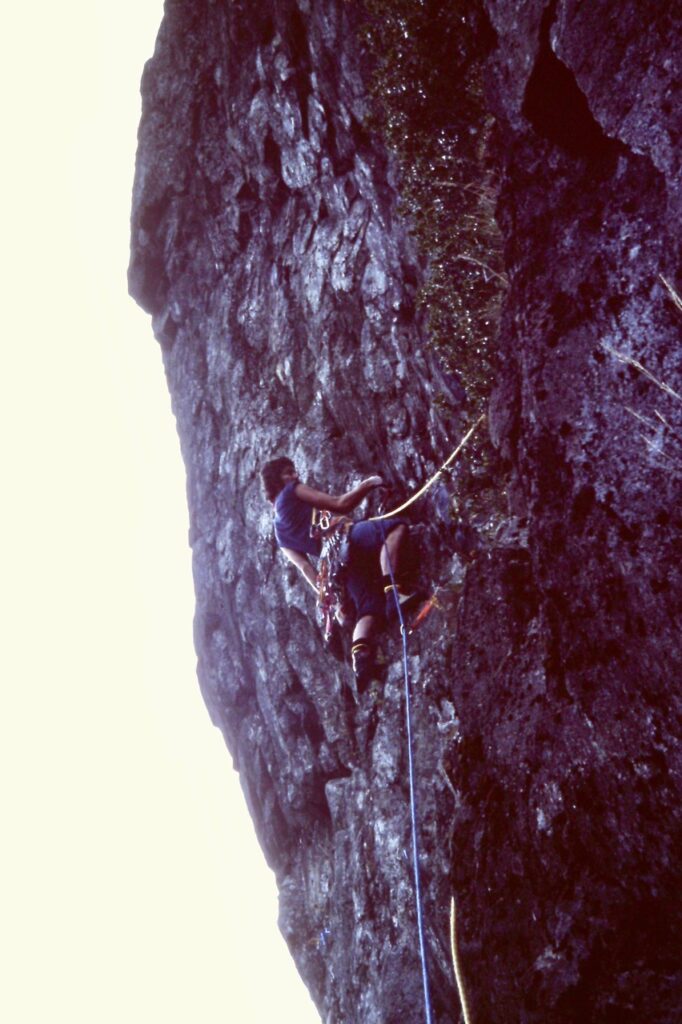

South Chimney, Dow Crag, circa 1960

South Chimney, Dow Crag, circa 1960

At this stage my Dad only went out occasionally, and usually with a friend, Neil. Both of them were learning the “ropes” as they went, with an old hemp rope, couple of slings and carabiners. I knew my Dad was concerned when he took me out, particularly when leading, and looking down to see his frail young son belaying him around the waist, as was the norm in those days. Falling was not an option and down-climbing an essential skill. Looking back this was one of the reasons I started leading so young — it was safer!!

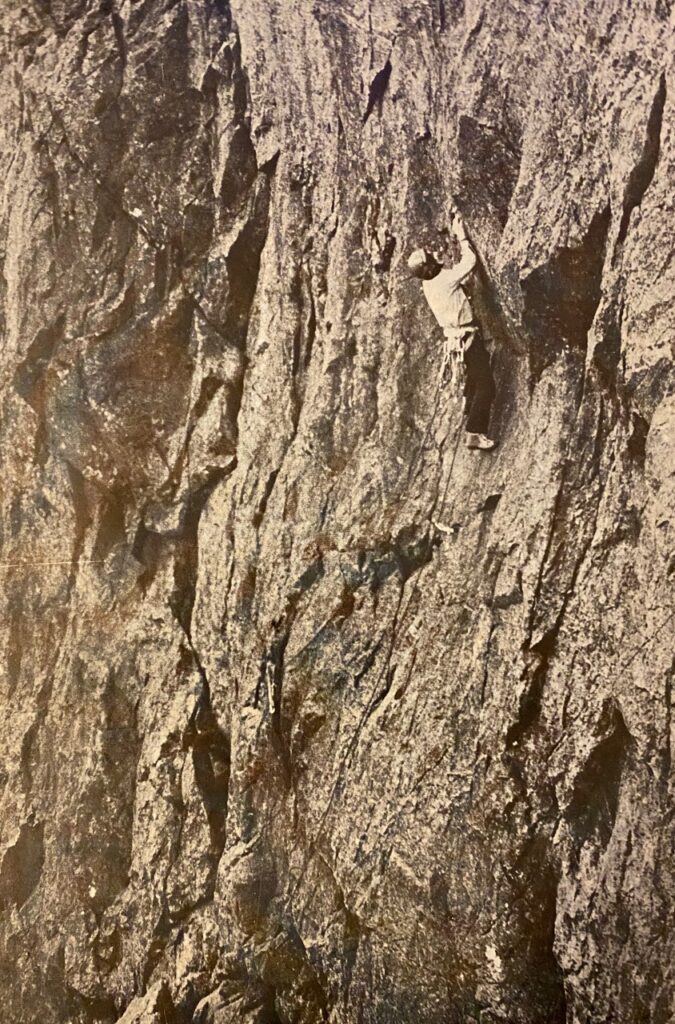

So gradually we moved up the grades, from Diff to V.Diff and even to Severe, which was a major event in our splendid isolation. The local guidebooks were getting ticked off and our gear was improving, all be it from shocking to bad. I had FEB big mountain boots and Dad some Kletterschu lightweights and when I was 15 and Dad 51 we hit the magic Very Severe grade with our ascent of Gimmer Crack. I’m sure this was when I really had to start and focus on footwork as my main means to progress up the grades — precise and silent feet!

We spent many long weekends and evenings climbing as a family, Dad, Mum and myself, mainly on Wallowbarrow Crag in the Duddon, Scout and Raven Crag in Langdale and of course on the mighty Dow Crag above Coniston. Our equipment was basic to say the least. We progressed from a borrowed hemp rope to a Viking 11mm nylon one, with some 9mm slings and a few Stubai and Cassin big D carabiners. Dad bought a few Moacs, which complimented our trusty collection of drilled out nuts. No harnesses — rope round the waist with the bowline knot. No belay plate — just behind your back with a twist round the bottom arm!! All the Diffs, V.Diffs we could lay our hands on . And then the first SEVERE at the age of 14. There was no holding us back and the rest of the climbing world was irrelevant.

My only aim was to do all the routes of that grade and I don’t remember aspiring to higher grades until I started going out climbing with some school mates when I was 16. Climbing walls didn’t exist and the idea of practising or training outside of the big crag environment never crossed my mind. By today’s standards we were physically weak, there was no doubt about that! But as far as crag craft and mental resilience goes I think we were strong, and this has been the foundation of my trad climbing progression.

Grade progression was very slow because everything was done ground up and on sight. There was no other way. Read the guide, find the start, gear up and go! Don’t do a move you can’t reverse. Become a protection expert but never test it. I never fell off in those early days! Today climbers fall all the time, as that is the measure of whether you’re trying or not, and often seen as the only way to progress. Early trad climbing was just a different ball game!

Family was a tight knit unit during your early climbing days and you weren’t really aware of what was going on in the outside climbing world. How did other climbers such as Ray McHaffie influence and shape your climbing?

It was on a trip to Shepherds crag in Borrowdale when my parents started talking to this local climber who was tearing all over the crag soloing everything in sight. He offered to take me up a climb so I jumped at the chance! He climbed so fast and didn’t seem to put any runners in! He told me his name was Ray and that he’d done some first ascents. We did Monolith Crack which was a Very Severe — a great leap forward in grade for me at the time. He told me to get some proper climbing boots so you could stand on “nothin’ “. He wore RDs so that was the way forward! So yes, the late, great, Ray McHaffie influenced me and gave me the confidence to lead my first VS a year later. I climbed with Ray once more many years later, when I got my own back, and took him up North Buttress, a tough E1, again on Shepherds. But I didn’t climb fast and did put some runners in!!

Another meeting of a “Great” was on Lower Falcon in Borrowdale when I was 16. I was leading Illusion HVS and was struggling to pull round onto the stance at the top of the crux pitch. I asked a climber at the bottom if he’d done the route, to which he replied “ Yes, did first ascent”. Well I didn’t have a clue who that was — all I wanted was some advice of where to go. “Just pull round onto the stance” and with that he disappeared! I was at the top of my grade and just couldn’t make the move so I down climbed the whole route taking the runners out on the way. My mate at the bottom said “That was Paul Ross you know!” The next time I met Paul Ross was 48 years later which goes to show how insular Lakeland climbing can be! Looking back I was never really into the history of climbing unlike some of my ‘guidebook Gary’ mates. I did climb with Ed Grindley a few times in Langdale and was aware of Alan Austin as he had done many of the harder first ascents. Obviously Joe Brown and Chris Bonnington did the odd lakes route but not until I started climbing in other parts of the country, later in the 60s, did I become aware of other personalities. My climbing outlook remained unchanged — start at the bottom and try and get to the top!

In your eyes what were some of the major Lakeland climbing events prior to your Paladin ascent?

At the time I was only aware of developments when they were published in the Fell and Rock guidebooks or some “pirate publications”. Prior to climbing Paladin I had climbed most of the hardest routes in the Lakes, many of which originally carried aid points. They were classic E1 and E2 but in the early 1960’s hard routes were just graded VS. Later in the decade HVS and Extremely Severe grades were introduced. Routes tended to follow cracks and grooves which favoured protection, certainly an advantage when pushing up ever steeper rock. I was not aware of top roping practices at this stage but Arthur Dolphin had top roped Kipling Groove before leading it, and that was in back in 1948!! I did find it interesting that in the early 60’s Alan Austin was top roping, practicing, then soloing E3’s on Yorkshire grit, such as Wall Of Horrors on Almscliffe, but would not resort to those practices on Lakeland rock, instead using the odd aid point, such as on Astra, the classic E2 on Pavey Ark . The Medlar on Raven Thirlmere had a fearsome reputation but even Boysen and Bonington had resorted to several points of aid. Way back in 1956 Ross and Lockey had even ‘forced’ Post Mortem on Eagle Crag in Borrowdale, a fearsome off width, that is rarely climbed, even today!

The Lakes was peculiar, in that climbers pushing the grades and developing crags tended to focus on their own patch, and in a way became protective of it. Outsiders came and pinched some ‘last great problems’ such as Geoff Oliver with the fantastic Ichabod on The East Buttress, Pete Crew with Central Pillar on Esk Buttress and the amazing contributions of Les Brown with Praying Mantis on Goat Crag, The Nazgul on Scafell and The Balrog and Sidewalk on Dow Crag. And, perhaps Lakelands first official E3, as no aid was reported for Richard McHardy’s ascent of The Vikings on Tophet Wall in 1969.

The locals were always beavering away and pushing the envelope, such as Ray McHaffie with the The Niche on Lower Falcon, the underestimated Iago on Heron Crag in Eskdale by Singleton and Jackman, and Geoff Cram’s ferocious Ghost on Castle Rock and the elegant Tomb on Gable Crag. The Johnny Adams / Colin Read team were always quietly influential with many notable efforts, including Athanor on Goat Crag and the amazing Lord of the Rings on East Buttress. This is by no means a comprehensive list and I apologise for any omissions but, looking back, virtually all of these routes were technically 5b/c, at the most, and aid kicked in when moves were sustained 5c or even hit 6a.

I had certainly done most of these routes by 1969 and will have done them according to the guidebook description of the time. If there was an aid point it was not in my psych at the time to try and dispense with it. I was just happy to tick off the routes. I do remember that Paladin seemed so much harder than anything I’d done but I did become obsessed that I had to be the one to get rid of the aid! Things certainly accelerated on that front in the early 70’s when climbers began to train, got stronger and, dare I say, more competitive! (For those wishing for a more comprehensive look into this era, when climbers were trying their best, by sheer amateur enthusiasm, rather than the more professional approach of the late 70’s. “Cumbrian Rock” by Trevor Jones/Geoff Milburn would be a good read.)

Can you give a rundown of the controversy with Alan Austin? What was his argument as to why he left your routes and other route out of the guide? How did it make you feel? When did Austin’s views become less mainstream and no longer the prevailing ethic?

In the early 1970s The Fell and Rock Climbing Club were in the process of writing the new official Langdale climbing guide. Alan Austin and Rod Valentine were compiling it — always a thankless task!! I had done Paladin, originally with aid, and subsequently free climbed it. A few months later I did a route on Deer Bield crag using a peg with a sling on it for aid but leaving all in place for future climbers to use. It was recorded honestly as The Graduate, but the original normal length sling got exaggerated over time to become “body length”. The sustained 6a barrier had been reached, hence the aid, and it was not dispensed with until 1979.

At the time I wasn’t bothered to go back as I was too busy socialising in my Year Off after Graduating! But in April 1972 I did the same thing on Cruel Sister on Pavey Ark by climbing the big overhang direct with a skyhook to reach the sling on the peg. The route now traverses in more easily above this controversial section, which for some reason I never thought of doing at the time. Anyway all hell let loose from the Fell and Rock hierarchy and what’s more, a climber called Pete Livesey was cutting in on the Lakeland domain using “professional inspection, pre- placed gear and practice techniques” developed on gritstone and limestone. All such routes were omitted from the new guidebook.

In 1972 I could see this brewing and Tim Lewis ,the editor of Rocksport, could see an opportunity to challenge the climbing establishment and published an article entitled “Poking In The Ashes – Lakeland Controversies” written by me, under the pseudonym of ‘Henry Ford’ — in opposition to Alan Austin!— that’s journalism I suppose! Ken Wilson of “mountain” magazine ran it in 1973 by publishing letters on the issue, with the profound quote from Alan Austin:

“I do not see crags as impressive backcloths where ruthless men can construct their climbs”

Great stuff.

I suppose we are allowed to be a little more ruthless today, but the aid has certainly disappeared, due to that conditioned strength of the top performers and the acceptance of top-roping and pre-practice. The only “sin” that remains, is pre-placed runners. Accepted as the red point norm in sport climbing but, dare I say, a particularly ruthless practice in Trad climbing. Perhaps I’ve come full circle in my dotage! Maybe it’s just that we personally get rid of those bits of ‘ruthlessness’ when it happens to suit us at the time, particularly when fear kicks in!

How did Lakeland climbing go on to change in the 1970s?

The 1970s saw grades creep up from E3 5c to E6 6b by the end of the decade. The amazing bold and gymnastic feats on northern outcrops, began to have an influence and the attacks on overhanging limestone picked up a pace. Climbers were more focussed and training of some sort became the norm for most of those pushing the boundaries.

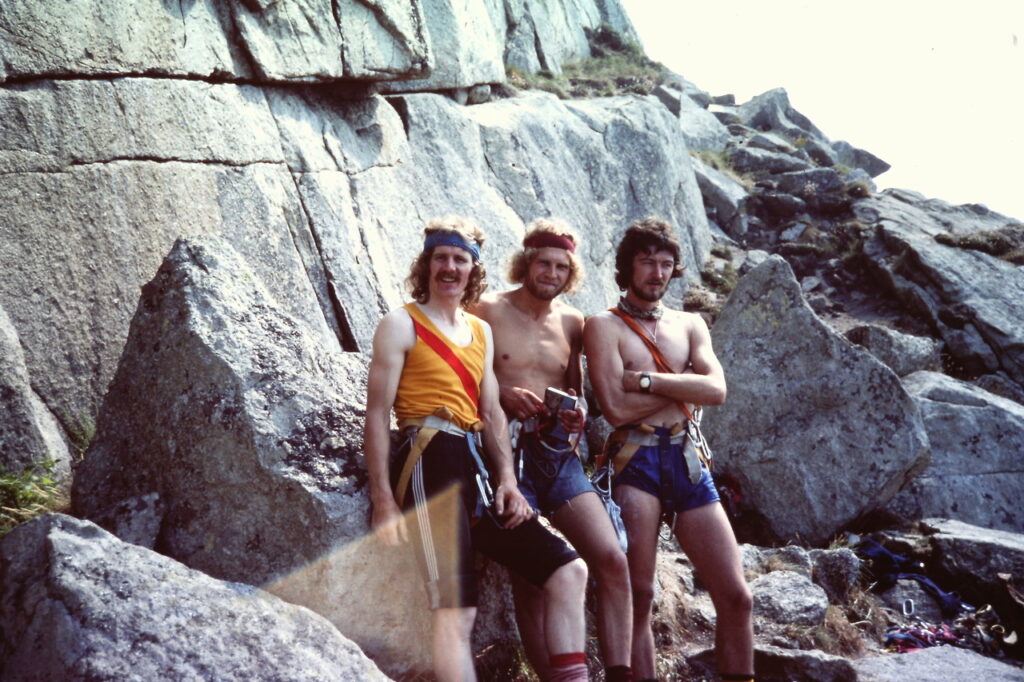

By the mid decade, chalk, in the form of ‘light magnesium carbonate’ bought from concerned chemists, became common, and in itself became a controversial issue. In the early 70’s I often used dry soil and became an expert in finding it! Back then my main focus was just to have a good time with my climbing mates which involved spending long summers in the alps, always on the edge of social acceptability, and climbing widely throughout the UK. I think most groups of climbers were initially like this in the early 70’s but things did begin to get a bit more ‘professional’ as the years passed and the age of the more serious athlete established itself.

I remember having a disagreement with Ed Grindley over a new line on Pavey Ark in 1973. I had cleaned the main pitch and hammered in a peg which I thought you’d need to protect it. Ed’s ethic was that any pegs had to be hammered in on the lead so he removed it and led the route, heroically placing it on the lead. Exhausted he had to slump, so recorded the route with a point of aid! Ed would have perhaps done Brain Damage free, if he’d just used my peg, but what’s important is that he followed his own standards and recorded the ascent honestly. This along with Ed’s other route, Fallen Angel, was certainly pushing that E4 barrier. [More detail on this era can be seen in my 1977 article in Mountain 54 “Lakeland Climbing in the ‘Seventies”]

It was at this time that Pete Livesey was starting to wield his talents. I was told, by a spy in Leeds, that he was coming up to Dow Crag to check out my route Holocaust E3 which I had climbed with aid in 1971. Dreading the worst I hid on easy terrace to watch, and when he slumped on the aid points, a delighted me appeared from my lair to converse with him. Thankfully he confirmed the grade and those aid points.

My mother met him later in the day and told me what a charming man he was and that she thought he was a good climber and that he had lots of projects he wanted to do in the Lakes!! The rest is history and no matter what opinion people had, and have to this day, on his “professional” approach those ‘Lakes projects’ turned into an impressive list of difficult classics such as Eastern Hammer E3, Footless Crow E5, Bitter Oasis E3, Dry Grasp E4, Tumble E4, Lost Horizons E4 and later, with Pete Gomersall, the yet harder, Peels of Laughter E5 and Das Kapital E5.

Were his early routes a step forward in difficulty? Only Footless Crow, which was later given E5, and soon to get harder, as holds kept falling off! Interestingly when I discussed the difficulties of the route with Pete, just after he’d done it, he said it was no harder than Bitter Oasis – E3!!?

The competition was ramping up in 1974 and in a race for the mega groove line on Esk Buttress, Rod Valentine and Tut Braithwaite forced The Cumbrian E4, resorting to 3 aid points. Unfortunately for Rod, he was directly linked to the Fell and Rock stance of the previous years, and now, he himself became one of the “ruthless men constructing their climbs”. I’m sure Shakespeare will have written about this sort of thing, but Rod Valentine is the nicest ‘villain’ you could ever wish to meet; giving it his best shot and being totally honest as to how it was done. It wasn’t free climbed for a further 3 years!

By 1975 a North/South divide was emerging, which seemed to get increasingly competitive towards the end of the decade. In the South Lakes patch I became aware of a young man called Ed Cleasby who let it be known that my routes were ‘easy’ as it only took him 15 minutes to dispatch Pink Panther on Dow Crag. Ed always used to time himself when leading a pitch! Part of his competitive psych I suppose. Being practical by nature Ed certainly became a protection expert and in 1976 we did our first new route together Grand Alliance E4 on Black crag. This was my line so I led it. My strengths; footwork and no runners! Ed had more physical strength, great determination and always had a sports plan!

We had a great time pioneering many new routes together, occasionally with John Eastham, and pushing towards that E5 6b barrier by the end of the decade, along with strong locals such as Bill Birkett, Rick Graham, Andy Hyslop and Ian Greenwood all of whom sampled the delights of Ed’s guidance and opinion at times.

From our perspective there was not a change of ethics in new routing. We abseiled and cleaned the lines but there was no top-roping or pre-placing gear, not even pegs! On a couple of occasions, on Shere Khan E4 and Mother Courage E3, Ed had slumped on a piece of gear after he had difficulty placing it, so was written up with aid. If we’d been more thorough in our inspection, of what gear was needed, no doubt it could have been a different story. We just recorded it as we found it on the day and I know this frustrated us when Ron Fawcett and then Jerry Peel dispensed with the rests.

This mindset, however, led us to an episode of ‘sinful behaviour’ a couple of months later! I had spent a long tiring day thoroughly cleaning a new line on Deer Bield Crag and Ed was keen to have a go at the end of the day. The gear was sparse and marginal, so he wanted to check it out for himself. To save energy and time, in the fading light, he top-roped up on my abseil rope, lowered off and led it. Imagination E4 6a. Well, strong words certainly flowed in our direction when Pete Whillance found out about the top rope, as this had, not only, been one of his favoured lines, but in his opinion, top roping was cheating and totally out of order! A couple of weeks later Ed put up a new route in White Ghyll called Ethics of War! Ah well, all I can say is that Pete Whillance carried such respect, that his opinion was not there to be ignored! I do not recall top roping again in this era! Ed certainly climbed more than me at this time, and regularly teamed up with others to produce classics such as Saxon E2 on Scafell and R&S Special E4 on Raven Crag Langdale and the elegant Equus E2 on Gimmer. One of our 1977 highlights together was when we on sighted the first ascent of Lubyanka E3 on Welsh soil, after a particularly long drinking session in the Padarn the night before!

So, back to the north/south divide. Those Carlisle boys were strong. And very driven. Fierce lines were unleashed by a combination of forces — Pete Botterill, Pete Whillance, Jeff Lamb, Steve Clegg, and Dave Armstrong. Not only were they doing high standard new routes, in and out of the Lakes, but busy eliminating aid from existing routes. Shadowfax E4, Explosion E3, Gates of Delirium E4, Creation E4, Eclipse E3, Supernatural E4, SOS E5, Equinox E4, Trilogy E4; the list goes on. Pete Botterill must have felt sorry for me after he and Jeff Lamb had found a way of avoiding the aid on Cruel Sister by traversing in above it. He reckoned you could do the same on Holocaust! Another of my routes; well I wasn’t having that! So I beat him to it by making a particularly dynamic dive across the crucial overhanging wall, ending up as a genuine 6a move. The Carlisle boys were often accompanied by Martin and Bob Berzins, as if they weren’t strong enough already! Dispensing with existing aid points was also one of their delights and The Cumbrian in 1977 comes immediately to mind. Their particular love was steep rock and classics such as Ringwraith E4/5, Cullinan E4, and Roaring Silence E3 on Scafell and the underrated Ataxia E4 on Flat Crags. Again that E5 grade was establishing itself by the end of the 70’s. Some would argue that you needed to add an E grade to Lakes routes — a 70’s E4 is tough!! And how can I not mention Ron Fawcett who made several visits to the Lakes culminating in 1979 with his siege of Hell’s Wall on Bowderstone Crag. E6 6c but, unlike most other hard Lakeland routes, it was well protected and totally safe, because of its aid route origins! Pushing the grades usually causes a change in the style of ascent and this siege tactic was not typical of the Lakeland scene. Nevertheless, it was absolutely nails and, move for move, harder than any other Lakes route of the 1970s.

What were some of your highlights over the next few years and further into your climbing career? How do you keep fit and motivated?

By the late 70’s and into the early 80’s I was losing that climbing obsession and by 1983 I’d virtually given up. I even had a period of insane potholing when Jonny Adams and myself hit some of the hardest potholes in the country — just for the challenge! We regarded potholing as a semi-skilled activity and as climbers found the hardest potholes ok. Our descent of Quaking Pot on Ingleborough was perhaps the highlight, as rescue beyond the crux was impossible and the whole trip could take up to 18 hours! You couldn’t get this type of climbing commitment in the UK and the drinking session in The Hill Inn afterwards was particularly memorable! At this time quite a few climbers spent winter months grovelling around underground and Pete Livesey had been a leading activist before concentrating on climbing. On one occasion I even met Ron Fawcett swimming in the liquid clay at the bottom of the classic Pippikin Pot and I asked him how he got those enormous hands of his through the squeeze!

So I missed the 1980’s climbing revolution and emerged in 1990 as a proficient windsurfer and squash player, two activities which had taken over my obsessions. I wasn’t even aware of what was going on in the climbing world; not even vaguely interested!

For a strange reason, one that I can’t even fathom today, I applied to get a place in the 1991 World Climbing Championships at Birmingham’s National Indoor Arena: for the over 40 age group of course! So I did some training on Alan Steele’s climbing wall in Ingleton on some stuff called Bendcrete and a few glued in crimps. Well, needless to say, I was nearly last. I couldn’t believe how steep the competition wall was, and when I was marched out from behind the curtain I was so overwhelmed I forgot to take my sweater off and lurched hastily upwards, getting immediately pumped in the process. In no time I took a ground sweeping fall, having failed to clip, through utter exhaustion! It was all a bit of a blur, but I do remember seeing those awesome Lancashire boys nearly topping out — Jerry Peel, Dave Barton, Barry Rawlinson — and they were even older than me! And still are!

The reality of being very average on an indoor wall hasn’t really changed over the years, even though I’ve become slightly more practised. But mediocrity can be a driving force, and my appetite for climbing once more returned. Throughout the 90’s I climbed with the “Barrow Boys” who were renowned for their loud banter wherever they went. Keith Phizacklea, (The Guru of Lakeland climbing) was one of the main driving forces in a group that regularly exceeded a dozen in number. I remember being allowed on an early visit to Ambleside Wall to get totally humiliated by muscular mutants such as Glen Sutcliffe and a finger crimping genius called Dave Birkett. The Barrow Boys climbed all over. And all the time. And usually on-sight. Personally I only broke this rule if I thought I could die, so before I soloed Slip and Slide E6 on Crookrise, in 1997, I dared to top rope it first. A slippery slope!

We travelled all over England, Scotland and Wales, on all types of rock. Certainly up to E5 on sight and ticked virtually everything within range. Some of the boys took to sport climbing and I could certainly see that they became a lot stronger. I tried it a few times but felt that trying a few moves for hours on end was a waste of a day! Even training in the evening at Ingleton Wall was becoming the norm and it was no surprise to see some of the boys pushing that magic 8a. In the meantime Craig, my eldest son, had done his first route, a Severe on Pot Scar at the age of sixteen and that I’m afraid was the start of his climbing obsession! A year later, in 1997 we both led Linden E6 on Curbar, after checking it out first, and then, after being chastised by Keith, for not on sighting, we both soloed Great Slab E3 on Froggatt, as if it were a punishment. Not sure I was setting the best of examples to my son!! Into the new century climbing continued in a similar vein with the trad/sport/bouldering mix. More than ever I became more aware of the necessity to maintain a high general fitness in the face of an ageing body. Having done most Trad routes within realistic grades it was a matter of picking off those I had never done. The Cad E6 on Gogarth was one and I distinctly remember it being quite well protected and probably a high end E4 by Lakeland standards.

I also remember doing some very bold E7s at this time, by thoroughly checking them out first. Examples were Dave Pegg’s Flattery on Flat Crags Bowfell and Moffatt’s De Quincy on Bowderstone Crag Borrowdale. After all I was over 50 and only the top boys were doing E7 on sight! I did have rules though — all gear had to be placed on the lead! I suppose this is now referred to as “headpointing”. But some climbers do still pre place runners — Oh No!!

The great release came in 2010 when I retired from teaching and sponsorship, in the form of a pension, enabled the full-time trained athlete to be unleashed! Now to get strong! After suffering from body weakness for years, and having the stress of work responsibilities lifted, I was ready — for injury! Oh yes, within weeks I was under the expertise of Mr Funk at Wrightington hospital with rotator cuff and elbow injuries. Strong advice followed and I was told I had to address my muscle group imbalances, mentioning muscles, tendons and ligaments I’d never heard of. So I protected my injury zones for the winter and focussed on improving my off-piste skiing technique instead. I was told that ‘climbers’ often ski leaning too far back due to a natural aversion to falling downhill!

It was a year later that I hit an important personal landmark. In 1982 Ron Fawcett had completely free climbed Cave Route Right Hand E6 in Gordale. I remember looking up at this, just after Ron led it, shaking my head in disbelief. I was totally disillusioned at being so far behind the leading pack and could never hope to climb anything like that. Shortly after, I gave up climbing completely. So, at the grand old age of 61, I returned and led it. On the same theme I managed Obsession F7B+, a classic on Malham, which I had failed to get anywhere near back in the 90’s and then a couple of years later, Hell’s Wall E6 on Bowderstone, Fawcett’s 1979 test piece which I never would have imagined ever being able to lead. Phoenix in Obsidian E7 on Iron Crag followed, but despite the grade, it felt much easier for me. Age is irrelevant until you get there. Why do older climbers always mention their age or others gleefully point it out? Climbers like Karl Telfer or Mick Lovatt, who’ve been around forever themselves, always greet me with “Bloody Hell, you still alive?” Terms of endearment I like to think! Youngsters just ignore your existence because they only ever see you on the wall, and you’re distinctly average anyway. In this age of “instant gratification” age and history just get in the way! But when I led a 7a+ in my trainers at Kendal wall last year a young UK hotshot talked to me afterwards — I knew I had made it! He had, of course, never climbed outside!

So where am I going with this? New horizons of getting more media savvy. I started filming some ascents with the purchase of a 1080p Panasonic camcorder. Angry Pensioner Productions. Some of the boys were particularly camera shy as it adversely affected their performance. But we persevered and have many hours of unseen footage. Some published episodes are an acquired taste and last far too long for most, unless you want that detailed breakdown of every move, which takes away that on sight experience. Such examples include; R‘n’S Special E5 on Raven Crag Langdale, Internal Combustion E6 on Raven Crag Threshwaite Cove and Western Union E6 on Iron Crag.

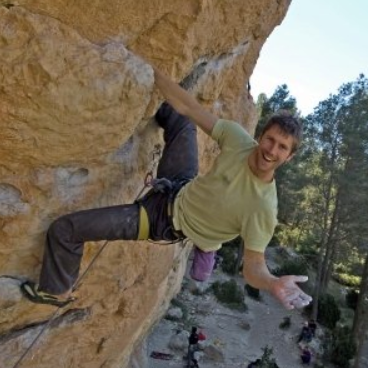

Shortly after my retirement Craig had returned from working away and had emerged somewhat more powerful. We climbed more and more as a separate team with focussed sports plans, whether new routes or existing challenges. Several grades apart I might add! Craig was focused on repeating the hardest routes in the Lakes, which inevitably meant repeating Dave Birkett E8/9’s. Unfortunately Craig’s work and young family commitments often meant one day a week on the crag so we always stayed local, if Scafell’s East Buttress can be classified as such.

Things were going great and then in September 2014 I had my first climbing accident. I was climbing over the roof above Laugh Not on White Ghyll and demonstrating, to Alan Steele, my new overhead heel-hooking skills. Then the finger hold snapped off and I plummeted onto the slab below, smashing my left ring finger, which was hanging uselessly over the back of my hand. At least it was out the way for climbing so I went up Laugh Not to the top, abseiled to get the gear, got some paracetamols from a couple at the bottom, walked down and drove to hospital. Three days later I was discharged, after an amazing bit of microsurgery to get my finger back. Problem was my arm was in plaster up to my arm pit and no climbing for a few months — on that arm anyway! The wise words of my grandad now come to mind: “Every setback is an opportunity.”

Fortunately a few of us had been leisure cycling for a couple of years so I decided to hire an indoor trainer called a Wattbike and train my heart and lungs for a few weeks. Unfortunately, my obsessive nature took over, and I trained like a demon. Unlike in climbing I was very scientific, and when I was able to ride outside I got professional training advice. I found out that my power output was quite competitive for my age group so did further performance testing. When you are a ‘driven’ type of person you should only compete when you can. So I bought a race bike and entered my first category F (65-69) road race in the Lincoln Wolds in July 2015.

There was about 40 in the race from all over the country. Trouble was I was against guys who’d been racing for most of their lives (including ex-pro riders) and had body shapes I’d never seen before. I started the race really well, following the marshall’s car all the way up the hill, at quite a pace. Nobody came past me. After a mile I was really pleased with myself, despite feeling heavy legged and tired battling the headwind. But then I heard this strange whooshing noise, as the whole peloton went past me on the outside, in a long line. I never saw them again! As they say “it’s all a learning curve.” My life became watts, cadence, sweetspot and threshold and like someone new to climbing, I had shiny and expensive gear. I really put myself through it and climbing again disappeared off my personal horizon. In just over 3 years I had 65 races, ending up on the podium in many and even winning at National level events. I learnt, that in a race, it didn’t matter how much strength or stamina you had. That would only get you to the finishing sprint in contention. You’d only win, or get on that podium, with that extra power. Most races ended up, after 40 or 50 miles, in a sprint finish, and to live that adrenalin surge, has been for me, an extremely hard won privilege. I worked really hard on my power for sprinting, something which I never did for climbing. To compete nationally I had to travel hundreds of miles most weekends and with such a hard and focussed training regime I eventually hit the wall in September 2018. I haven’t been on a bike since! But.., it comes back to this matter of ‘power’. Without it, you hit your ceiling (in whatever sport) quicker than your aspirations want you to. Sport climbers and boulderers will be particularly aware of this, as they operate at their limits most of the time.

In 2019 I started to spend more time back climbing and my visits to Cam Crag on Wasdale screes were particularly pleasing but a lot of effort. I managed to create a future classic, Scarface E6, which has seen two repeats, confirming its quality and difficulty. (video link).

Personally, as I move into my 70s, I want to continue my 8 week blocks of ‘steady state’ training, as this is keeping me injury free, and enables me to work on my weakest muscle groups. This also involves working on that creeping stiffness in those joints and hip flexors – this has honestly helped massively! Recently I’ve had long discussions with Neil Gresham about training my weaknesses, which has been really useful in developing strategies, no matter what age, or grade you are aspiring to.

Motivation is another force which I constantly have to work on. It’s all very well having a wish list or desire, but the real test is getting off your backside, often when it doesn’t particularly suit, and taking a positive move in the direction of your goal, which may well be to walk up to Scafell in the pouring rain and abseil down that new line you have often thought about. The advantage of having climbed for so long is that some of my early first ascents, such as Paladin, Cruel Sister and Holocaust are up for 50 year anniversary ascents which is, of course, purely personal. This is likely to get more challenging as the years progress and grades increase! And an E7 at 70 seems poetic!

As I get older it seems even more important to maintain that drive and focus, and do what you can to stem that southerly flow.

Comments are closed